When patients go to see Dr. C.T. Lin for a checkup, they don’t see just Dr. Lin. They see Dr. Lin and Becky.

Becky Peterson, the medical assistant who works with Lin, sits down with patients first and asks them about their symptoms and medical history—questions Lin used to ask. When Lin comes in the room, she stays to take notes and cue up orders for tests and services such as physical therapy. When he leaves, she makes sure the patient understands his instructions.

The division of labor lets Lin stay focused on listening to patients and solving problems. “Now I’m just left with the assessment and the plan—the medical decisions—which is really my job,” Lin says in a quiet moment after seeing a patient at the Denver clinic where he works.

For generations, when Americans sought health care, they went to see their family doctor. But these days, they’ll often sit down with a physician assistant or nurse practitioner instead. Or they’ll spend a large part of their visit talking to a non-doctor, like Peterson, who takes care of an increasing number of tasks doctors used to handle.

Driven by efforts to control costs and improve outcomes, it’s one of the biggest shifts in the American health care workforce. Medicine increasingly looks like team sport, with duties and jobs that used to fall to a family doctor now executed by a team, from nurses who sit down with patients to discuss diet and exercise to clinical pharmacists who monitor a patient’s medication. The doctor, in this model, is a kind of quarterback, overseeing care plans, stepping in mostly for the toughest cases and most difficult decisions.

Under some models, the doctor may recede even further into the background, leaving advanced practice nurses or other highly qualified professionals in charge.

It’s no longer true “that you’re a sole cowboy out there, saving the patient on your own,” says Mark Earnest, head of internal medicine at the University of Colorado medical school.

The shifting role of doctors is expected to accelerate in the coming decades, as the number of older Americans increases dramatically, many of them living longer with chronic diseases that need monitoring but not necessarily the expensive attention of a physician at every visit.

This isn’t the job many physicians trained for—or that some want. Even doctors who support team-based care have trouble adjusting to the new workflow. Some don’t like the idea that they aren’t always the ones in charge. Others, sick of the industry pressures, are opting out and setting up independent practices that don’t accept health insurance.

But most doctors will have to adapt. Change is coming, regardless of the fate of the Affordable Care Act or other laws designed to reward health systems for outcomes rather than the number of procedures performed, says Randall Wilson, an associate research director for Jobs for the Future, a nonprofit that advocates for increasing job skills. “People see the writing on the wall,” he says.

New models

Americans spend more on health care than people in other wealthy nations. Yet Americans live shorter lives and are more likely to be obese or hospitalized for chronic conditions, such as asthma or diabetes.

Health care experts have long blamed these lousy results on our fragmented health care system. Americans rely on a mix of specialists and settings for care, but those pieces of the health care system don’t necessarily communicate or coordinate with each other.

They also blame the high costs partly on the fee-for-service payment system, which rewards hospitals, clinics and doctors for the volume of procedures they provide. Health insurers will pay for a patient sit down with a doctor. What they sometimes don’t pay for are other services that help patients stay healthy, such as a visit from a community health or a phone call with a nurse. Yet such services can prevent medical emergencies and save her and her insurer a lot of money on expensive treatments.

New payment models encourage health systems to deploy their workers more efficiently — while also avoiding unnecessary services and costly errors. For instance, Medicare already gives some hospitals a single payment to cover everything that happens to a patient from the moment he enters a hospital for knee replacement surgery to three months after he goes home.

Distributing work across team members can help keep costs down, relieve doctors of the busywork that jams up their day, and make everyone more productive.

At least, that’s the idea. There isn’t yet strong research that proves teams provide better or cheaper care, says Erin Fraher, director of the Carolina Health Workforce Research Center, a national research center at the University of North Carolina. Studies do show that nurse practitioners can deliver care as well as physicians, “but talking about substitution of one provider for another is not team-based care,” she says.

Major physician associations support improving teamwork and collaboration among health care professionals. So do medical school leaders. For some years now, accreditors have required colleges and universities that train doctors, nurses, pharmacists, dentists and public health experts to teach students to work in interprofessional teams.

But when it comes to the question of who is in charge, that’s where friction arises. Many doctors aren’t comfortable with the idea that they don’t always need to be in charge. The American College of Physicians will say a physician must always lead care teams, says Ken Shine, professor of medicine at the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin, but he disagrees.

“My argument is there are situations where another health professional needs to be directing the team,” Shine says. For instance, a nutritionist could create and manage a care plan for a diabetic patient.

Medical associations have also pushed back against proposals to expand the medical decisions non-doctors are able to do make on their own. Health professionals’ so-called “scope of practice” is governed by laws that vary from state to state. “While some scope expansions may be appropriate, others definitely are not,” the American Medical Association says on its website.

In a statement, the association says it “encourages physician-led health care teams that utilize the unique knowledge and valuable contributions of all clinicians to enhance patient outcomes.” It noted that top hospital systems are using physician-led teams to improve patients’ health while reducing costs.

To be sure, doctors aren’t being displaced anytime soon. But shifting tasks to other professionals reduces the need to train so many of them. According to a study by the Rand Corporation, a nonpartisan think tank, a standard primary care team model requires about 7 doctors per 10,000 patients. Increasing the numbers of nurse practitioners and physician assistants can drop that ratio to six doctors per 10,000, and in clinics run by highly trained nurses (known as nurse-managed health centers) the ratio drops to less than one doctor per 10,000.

Culture Change

Hospital systems like UCHealth, the University of Colorado-affiliated system where Lin and Peterson work, are betting that the future of health care involves a mix of professionals sharing responsibility for patients. Doctors will still run the show, but they’ll have to give up some control.

That culture change makes many doctors uneasy at first. Doctors want to protect their one-one-one relationship with patients. They may not understand what their non-physician colleagues have been trained to do, or are legally able to do. And many worry that change will make them even busier, by forcing them to manage the lower-credentialed professionals around them.

Lin is the chief information officer for UCHealth. As an administrator, he’s always pushing for change—his latest project is a system that releases certain test results to patients in real time. But as a practicing doctor, he also understands that change is hard.

He says that having Peterson in the examination room with him took some getting used to. “Like many doctors, I have a fear of letting go of all the things I traditionally do,” he says. That includes documenting a visit. “I’m getting over it, because I don’t want to be the only one here at 8 o’clock at night, typing.”

Matt Moles, a doctor who practices in the same clinic, says he also initially felt uncomfortable. Sharing the examination room went against his medical training, he says: “We’re trained to trust no one.”

It’s still possible for doctors to have jobs that resemble the Norman Rockwell era of long consultations—if they’re willing to opt out of the mainstream. A small but growing number are setting up or joining practices that, rather than taking health insurance, charge patients a monthly fee—typically around $75— for unlimited visits.

“I personally have the mentality of—leave me alone, I’ll take care of my patients,” says Dr. Cory Carroll, when reached by phone at his family care practice in Fort Collins, Colorado. He’s been a solo practitioner for most of his 25-year career.

Carroll has about 300 patients, a fraction of the patient load of a typical doctor in a big health care system. He sits with patients for over an hour if he has to. He visits them at home. He helps them connect with social services and community organizations. And he can focus on what he loves most: teaching patients to eat a healthier diet.

His practice is proof that it’s still possible for a family doctor to do it all. But he emphasizes that his experience is unusual. “I’m absolutely an outlier,” he says. Less than a quarter of all internal medicine doctors in the U.S. have a solo practice, according to the American Medical Association’s latest survey. And although the model Carroll has embraced is growing, it serves a more affluent slice of the patient population than a major hospital system such as UCHealth.

The team-based future

UCHealth’s leaders are so sure that team-based care is the future that newly built clinics, such as the one in Denver’s Lowry neighborhood at which Lin and Peterson work, are literally built for teamwork. Examination rooms don’t line long hallways; instead, they ring desk space where nurses, physicians and medical assistants sit side-by-side.

But the clinic is still in the early stages of transforming its teams. The best place in Denver to watch a diverse set of health professionals working together is across town, at a facility run by Denver Health, the city’s public safety-net hospital system. The facility includes a primary care clinic, an urgent care center and a pharmacy.

One recent morning, the distant wail of a baby in the waiting room announced the start of another busy day. Doctors, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and medical assistants were already typing away at the computers in their cubicles, trying to get a head start before the first patients were shown in to examination rooms.

“A lot of Denver Health patients are so complex,” explains Dr. Benjamin Feijoo, looking up from his desk. Patients often have multiple health issues, too many to handle in a typical 20-minute visit. “It’s a bit of a crunch,” he says.

So Feijoo turns to his colleagues for help. For instance, if a patient has both a medical and a mental health issue, Feijoo can address the medical problem and then ask a mental health specialist to step into the examination room and tackle the mental health problem.

If a patient needs, say, a crash course on prenatal health, she can meet with a nurse for an hourlong discussion. And if a living situation is compromising a patient’s health—such as unstable housing, or insufficient access to healthy food—the clinic’s social worker will try to find a solution.

The clinic also employs two community health workers, who spread the word about Denver Health in low-income neighborhoods, and a patient navigator, who calls the clinic’s patients when they leave a Denver Health hospital (and, for a subset of patients, other major local hospitals) and helps them schedule a follow-up appointment with their primary care provider.

Denver Health began expanding its care teams in 2012, when it received a $20 million federal grant. The system spent about half the money on hiring staff such as social workers, patient navigators and clinical pharmacists and the rest on software that identifies patients who are spending avoidable time in the hospital, including people who are homeless or have a serious but treatable condition, such as HIV. New, smaller clinics wrap even more services around those patients, allowing them to come in for multi-hour visits.

The new system now saves Denver Health—an integrated system, which includes a health plan—so much money on hospital stays and emergency room visits that it covers the salaries of the additional hires, says Tracy Johnson, the director of health reform initiatives for the system.

Reconfiguring care teams has made financial sense for UCHealth, too. Although the clinic where Lin and Peterson work has roughly twice as many medical assistants today as it had a year ago—plus a social worker and nurse manager—the configuration saves doctors so much time that they’re able to see more patients each day. The extra visits bring in enough money to cover the cost of adding more employees.

“The reason a lot of this happened is physician burnout was significant, especially in primary care,” says Dr. Carmen Lewis, the medical director of the Lowry clinic. The redesigned teams launched earlier this year aim to make doctors’ lives less stressful.

Patients across the UCHealth system don’t seem to mind the change. A few will ask to speak with their doctor in private, but others are more open with the medical assistant than with their doctor. “Sometimes, they don’t feel as judged,” Peterson says.

Lin says that since he’s started working with Peterson, his patients have been better able to keep their blood pressure and diabetes under control. “Patients will forget to tell me that they’re out of prescriptions,” he says—or he’ll be so busy tackling a more immediate problem that he’ll forget to ask.

With a medical assistant methodically asking all the opening questions, crucial details such as prescription renewals no longer slip through the cracks.

Rethinking medical school

Medical school leaders want to make sure the next generation of doctors has the skills and mind-set the jobs of the future will require—such as the ability to lead teams effectively, draw insights from data sets and guide patients through a system full of bewildering treatments, care settings and payment options.

Students traditionally spend the first two years of medical school learning science in classrooms and two years getting hands-on experience at clinical sites. That’s no longer enough, says Susan Skochelak, group vice president for medical education at the American Medical Association.

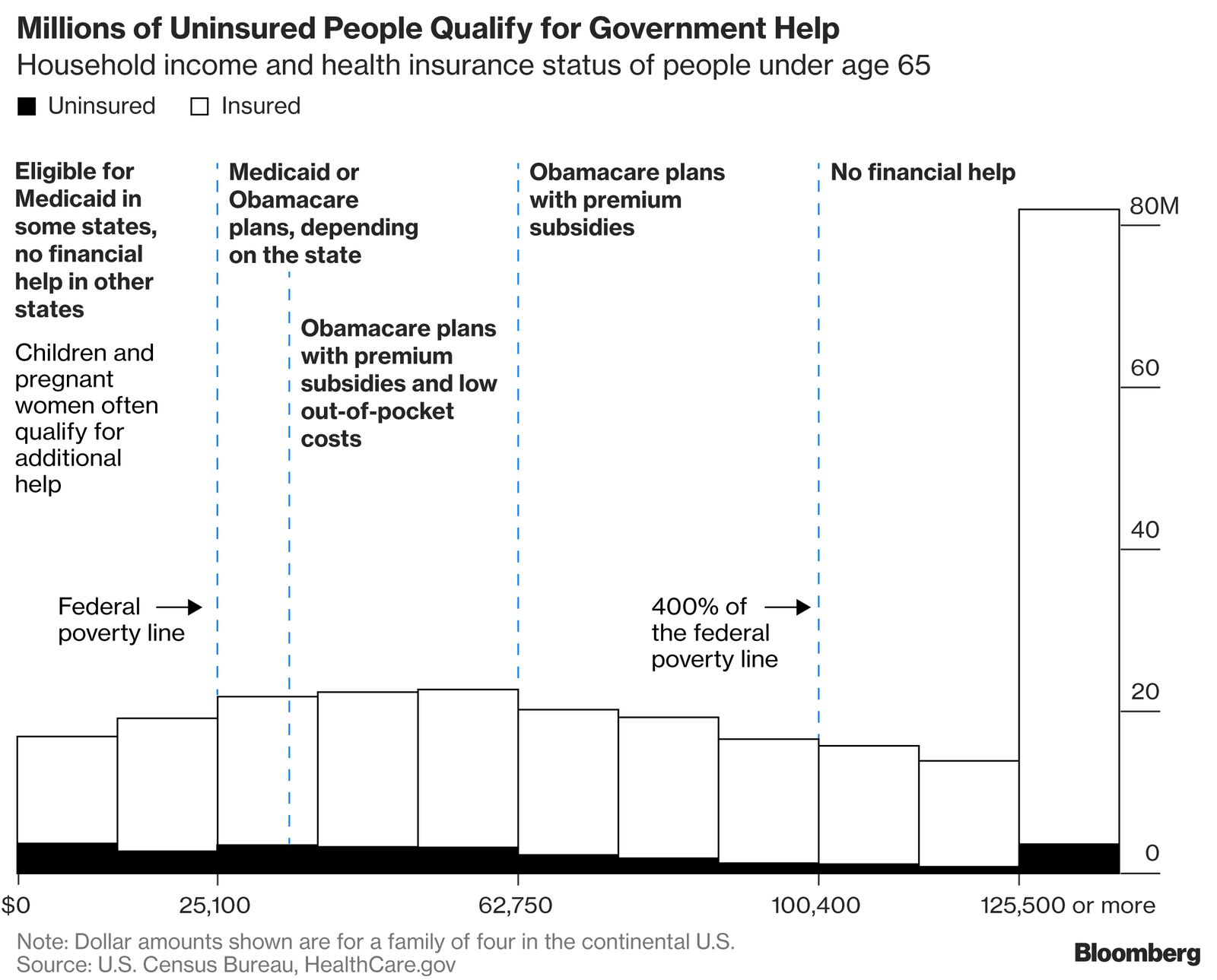

She says students need to understand “health system science”—everything from how health insurance works to how factors such as income and education affect health. “We had medical students who were graduating, not knowing the difference between Medicare and Medicaid,” she says.

So in 2013 the AMA began issuing grants to medical schools that wanted to do things differently. One program allowed Indiana University to put anonymous patient data into an electronic health record students can use to search for clues to a patient’s health—such as whether he is showing signs of opioid addiction. Another grant allowed Pennsylvania State University to create a new curriculum that requires medical students to work as patient navigators.

“Brand new medical students—they totally get the need for this,” says Robert Pendleton, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah and the university hospital system’s chief medical quality officer. At this year’s kickoff for an elective curriculum on data and performance measurement, he says, students packed the auditorium.

And all medical schools are trying to emphasize teamwork. At the University of Colorado medical school, the idea that doctors should treat non-doctors as partners—not subordinates—is impressed on students from Day One, says Harin Parikh, a second-year student.

The medical school shares a campus with education programs for six other health professions. Students hang out on the same quad, grab lunch in the same places, and even take some classes together. In a required first-year class, students from a mix of health fields are split into teams and are asked to plan a response to given scenarios. One day, a nursing student might lead the team; the next, a pharmacy student.

Parikh says the team-based approach makes sense to him. “From a provider perspective, it’s about checks and balances,” he says. When multiple people, with different kinds of expertise, come together around a patient, one may notice something the others don’t.

Reorienting medical schools, like reorienting hospital systems, will take time. Scheduling barriers can make it hard to get students from different health fields in one room, for instance. Some faculty members aren’t prepared to teach a new kind of curriculum. And when students leave school for their clinical training, they work in real-life settings that are all over the spectrum when it comes to teamwork.

“We’re working on an ideal,” says John Luk, assistant dean for interprofessional integration at the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin. “But the reality is, many of us have not been practicing at the ideal.”

Author: Sophie Quinton is a reporter for Stateline, a nonprofit journalism project funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Recent Comments