Why Some Americans Are Risking It and Skipping Health Insurance

Preparing Doctors to Meet the Demands of the Nation’s Changing Healthcare System

Prices and deductibles are rising. Networks are shrinking. And even some well-off Americans are questioning what they’re paying for. While the share of Americans without health insurance is near historic lows four years after the Affordable Care Act extended coverage to almost 20 million people, the Trump administration has been rolling back parts of the law. At the same time, the cost for many people to buy a health plan—if they don’t get it from a job or the government—is higher than ever.

In tiny Marion, North Carolina, the Buchanans decided that $1,800 a month was too much to pay for health insurance, and are going without it for the first time in their lives.

In Harahan, one bend of the Mississippi River up from New Orleans, the Owenses looked at their doubling insurance premiums and decided no, as well. “We’re not poor people but we can’t afford health insurance,” Mimi Owens said.

And in a Phoenix suburb, the Bobbies and their son Joey will go uninsured so the family can save money to cover their nine-year-old daughter Sophia, who was born with five heart defects.

Across America there are thousands of people like the Buchanans, the Owenses and the Bobbies making the same hard decision to go without health insurance, despite the benefits. They’re risking it—betting that they’ve got enough savings, enough of a back-up plan, or enough luck to get them through a twisted knee, a cancer, or a car wreck.

Bloomberg is following a dozen of these families this year in an effort to understand the trade-offs when a dollar spent on health insurance can’t be spent on something else. Some are financially comfortable. Others are scraping by.

While the share of Americans without health insurance is near historic lows four years after the Affordable Care Act extended coverage to almost 20 million people, the Trump administration has been rolling back parts of the law. At the same time, the cost for many people to buy a health plan—if they don’t get it from a job or the government—is higher than ever.

No one had to tell the Buchanans about the risk. Dianna, 51, survived a bout with cancer 15 years ago. Keith, 48, has high blood pressure and takes testosterone shots. They live in Marion, North Carolina, and make more than $127,000 a year from the small IT business Keith runs and Dianna’s job as a physical therapy assistant, with some additional income from properties they own. That puts them in the top fifth of households by income.

But their insurance premium was $1,691 a month last year, triple their mortgage payment—and was going up to $1,813 this year. They also had a $5,000 per-person deductible, meaning that having and using their coverage could cost more than $30,000.

What sealed the deal was when Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina and the major hospital system in Asheville, Mission Health, couldn’t reach an agreement, putting the hospital out of network. Keith Buchanan compared the fight to a cable company battling with a broadcaster over what channels to carry.

“It was just two greed monsters fighting over money,” he said. “They’re both doing well, and the patients are the ones that come up short.”

Blue Cross and the hospital eventually made a deal, but enough was enough for the Buchanans. Instead of insurance, they’re paying $198 a month for membership in a local doctors’ practice. They get unlimited office visits and discounts on medications and lab tests. They also signed up for Liberty Health Share, a Christian group that pools members’ money to help pay for medical costs. Liberty costs $450 a month, including a $150 surcharge based on the couple’s blood pressure and weight.

Three days after dropping their Blue Cross coverage at the start of the year, Keith took a wrong step and injured his knee.

It could have been worse. He got it checked out at an urgent care center, where the visit and an X-ray cost him $511. That’s still less than he was paying in premiums to Blue Cross.

“If we can control our health-care costs for a couple of years, the difference that makes on our household income is phenomenal,” Buchanan said. The couple doesn’t have children.

There’s plenty of evidence that having insurance is a good thing. People with health coverage spend less out of pocket on medical care and are less likely to go bankrupt. They see the doctor more often and get more preventive care. They’re less depressed and tell researchers they feel healthier. Some studies suggest having insurance reduces the likelihood of death.

Despite those benefits, some 27.5 million Americans under age 65 were uninsured in 2016, about 10 percent of that population, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The most common reason: the cost was too high. A Gallup poll suggests that, after declining for years, the percentage of adults without coverage has increased slightlysince the end of 2016, when President Donald Trump was elected promised to dismantle Obamacare. Other data show no significant change.

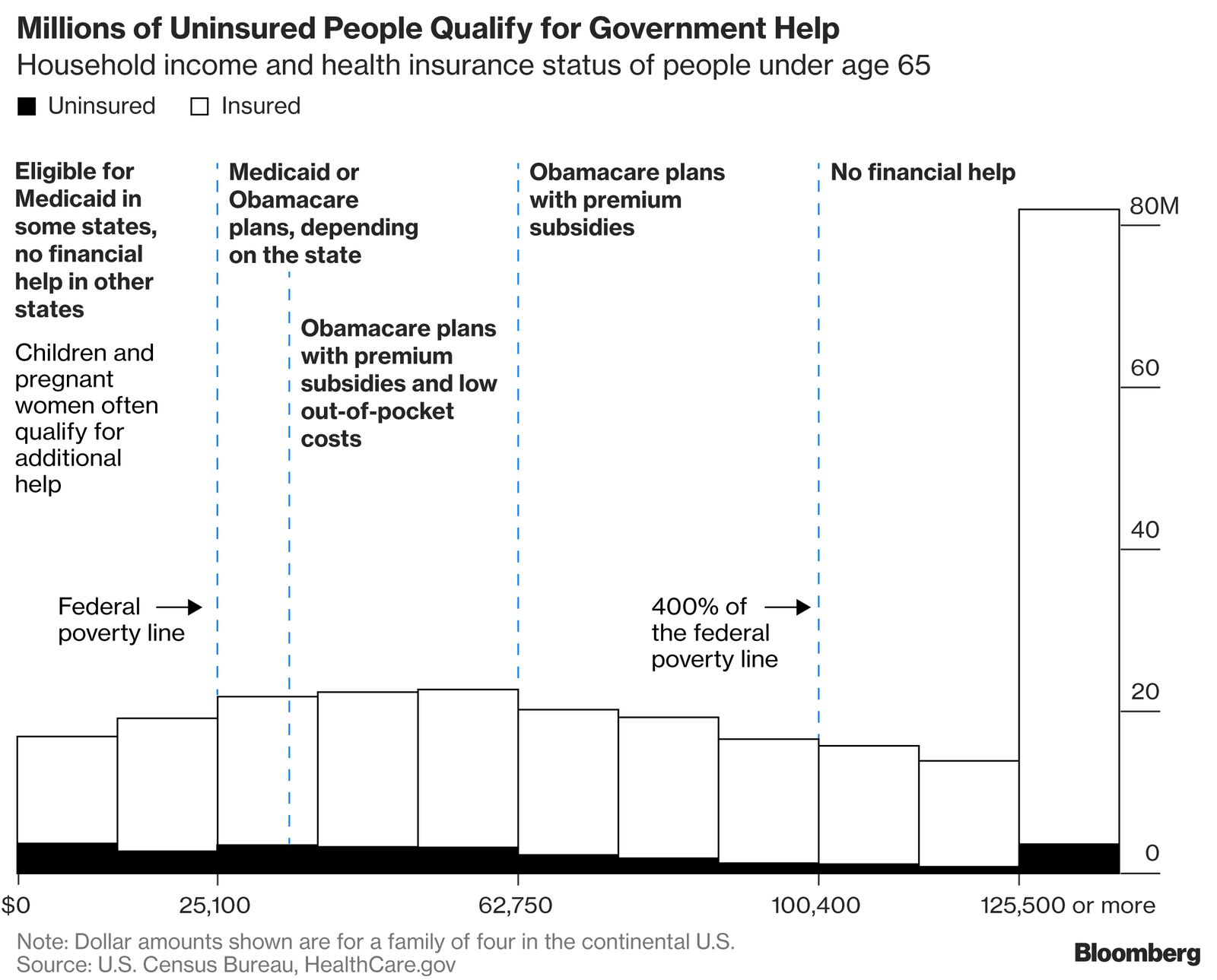

The Affordable Care Act wasn’t just an expansion of insurance coverage. It also rearranged how Americans’ medical costs are distributed, favoring some and asking others to pay more.

People near the poverty line got Medicaid for free, while those making more—up to about $100,000 for a family of four—got subsidies to lower the price of private health plans.

Above that threshold, people pay the entire price. Because the law barred insurance companies from charging sick people more or refusing to cover them entirely, costs for healthy people went up as well. Some insurers have left the market, while others have sharply raised premiums to compensate for actions taken by Congress and the administration to weaken the law.

The Bobbie family remembers the problems that the ACA was intended to solve.

Their daughter Sophia was born with serious heart defects, and the organs inside her tiny abdomen were in all the wrong places. She spent the first two weeks of her life in a neonatal intensive care unit. On her six-month birthday, she had open-heart surgery. At nine months, doctors operated on her stomach.

Sophia qualified for Arizona’s Medicaid program. But when she turned 2, the Bobbies were told they made too much money for her to get low-cost state coverage. Her father Joe Bobbie, who co-owns a Philly steak shop with his brother, reduced his take-home pay so Sophia would still qualify.

She had another heart operation just before she turned 3. In just a few short years, her parents were told, Sophia’s medical costs had come to well over $1 million. Before the ACA, no private insurer was willing to cover Sophia’s pre-existing conditions.

“Every door, every option, everything was just slammed in our face,” Sophia’s mother, Corinne, said. Medical costs that insurance didn’t cover piled up. The family skipped vacations and nights out, and lost their house and car because they couldn’t make the payments.

Those sacrifices have been tough on the Bobbies, but they’ve let Sophia have a relatively normal life. She takes medication for blood pressure and blood-thinners, and a daily antibiotic because she was born without a spleen. She goes to school, rides horses, and plays piano. A recent tumble from her horse frightened her mom, but Sophia jumped up and climbed right back on.

When Obamacare coverage became available in 2014, the Bobbies, who made about $55,000 last year, bought a policy for Sophia that now costs $217 a month.

Adding Sophia’s seven-year-old little brother Joey, who’s healthy, would have cost another $160 per month, with a $6,000 deductible. So he’s uninsured, and so are Joe and Corinne. The money they save risking their own medical and financial health goes to paying Sophia’s bills.

“Every single decision that you make has to be very carefully calculated so that your finances don’t fall apart,” Corinne Bobbie said.

The Trump administration proposes to make it easier for Americans to buy cheaper health plans, which could open more affordable options for the rest of the Bobbie family. But those less-expensive choices, such as short-term health plans, would lack some of the consumer protections created by the Affordable Care Act that allowed Sophia to get coverage in the first place.

The tax proposal that became law in December will also lift the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that every American have coverage or pay a fine. Economists warn that these changes could further weaken insurance markets, pushing up costs for sick patients like Sophia—and forcing more people into similar choices.

Some states are already trying out the new rules, offering plans that don’t adhere to ACA’s requirements. In Idaho, the state’s Blue Cross insurer attempted to offer a “Freedom Plan” with annual limits on care and questionnaires that would let it charge higher premiums to people who are sick or likely to become so. The Trump administration reluctantly judged that such a plan would violate Obamacare’s rules. But federal officials encouraged Idaho to explore offering similar policies as short-term plans that can offer skimpier benefits and lower prices.

In Harahan, Louisiana, outside New Orleans, Mimi Owens learned this year that her family’s $750-a-month plan with Humana Inc. was being discontinued. A new plan for her two daughters and husband on the ACA market would cost close to $1,600. Their family makes about $147,000 from a small business selling class rings and gowns to schools.

Owens said they go to the doctor “for a sniffle, for a flu,” and have a few regular prescriptions, so they looked into short-term health plans and tried out a Christian health-sharing ministry for a few months. The best solution she’s found so far is paying $130 a month to join a direct-primary-care group, which she calls “the best care we’ve ever had.”

It doesn’t cover the big things, though. An accident like a car crash could wipe out their finances.

“We were raised to have insurance,” Owens said. “This is crazy to us.”

Recent Comments