How Systems Engineering Can Help Fix Health Care

How Systems Engineering Can Help Fix Health Care

Critics have long faulted U.S. medical education for being hidebound, imperious and out of touch with modern health-care needs. The core structure of medical school—two years of basic science followed by two years of clinical work—has been in place since 1910.

Now a wave of innovation is sweeping through medical schools, much of it aimed at producing young doctors who are better prepared to meet the demands of the nation’s changing health-care system.

When an aircraft manufacturer decides to create a new model, it doesn’t ask pilots and crew to identify the best cabin, wings, jet engines, and other parts, and then put all the pieces together. A plane developed that way wouldn’t fly. The company begins with a goal, such as safely carrying 250 passengers nonstop from New York to London in under six hours, and follows a disciplined approach to identify the components and subsystems that meet those requirements.

By contrast, the way we build hospitals and clinics typically happens in a piecemeal, patchwork approach. Institutions purchase hundreds of individual, siloed technologies — each with its own work processes, training, and user interfaces — based on what the market offers. We then plop them into an ICU or operating room and hope that they somehow work together.

The result is a constellation of technologies that rarely connect, to the detriment of patient safety, quality, and value. For example:

- Different monitors emit alarms that compete with one another for the attention of clinicians, who must sort out which signify serious conditions and which don’t. Sometimes they miss critical alarms amid the noise.

- Devices, electronic medical records, and even patient beds have electronic information that can help diagnose conditions and assess risks. However, clinicians must consult each one individually, rather than seeing a unified display of information from them.

- Time that could be spent with patients and their loved ones is instead squandered in front of computer monitors, as clinicians click through dozens of screens in search of relevant information.

All of this leads to needless patient harm, low productivity, excessive costs, and clinician burnout. Doctors and nurses feel as though they’re serving technology, not the other way around. Preventing complications, errors, and other harm too often depends on the heroism of clinicians rather than the design of safe systems.

We need a new approach, one that puts the needs of patients and clinicians first. We need to integrate technology, people, and processes so that they are seamlessly joined in pursuit of a shared goal.

While this is new for health care, it has become routine in other complex, high-risk fields. It is the realm of systems engineering, a field that has contributed to jaw-dropping achievements, such as sending a spacecraft on a nine-year voyage to Pluto and designing a nuclear submarine.

These projects would not have succeeded without clearly defined, measurable goals and a rigorous approach for achieving them.

At Johns Hopkins, we experienced how powerful systems engineering can be when we set out to improve patient safety and quality of care in intensive care units. Patient safety researchers and clinicians from Johns Hopkins Medicine partnered with the systems engineers and systems integrators of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). For 75 years APL has supported the Department of Defense and other government agencies as a “trusted agent” to solve critical challenges, such as building satellites and weapons systems on ships.

The APL team guided patients, family members, clinicians, and researchers from nearly 20 medical disciplines through an exhaustive process of defining our goals, understanding our priorities, listing the functions that the system must perform, and determining measures of success. These discussions led us to set the goal of reducing seven of the most common and serious preventable harms facing ICU patients. They included five clinical harms, such as hospital-acquired infections and complications, as well as two “social harms,” lack of respect and misalignment of care with the patient’s goals. No doubt, patients are at risk for more than seven harms. But we had to focus because the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, which funded the project, wanted to ensure that we demonstrated results.

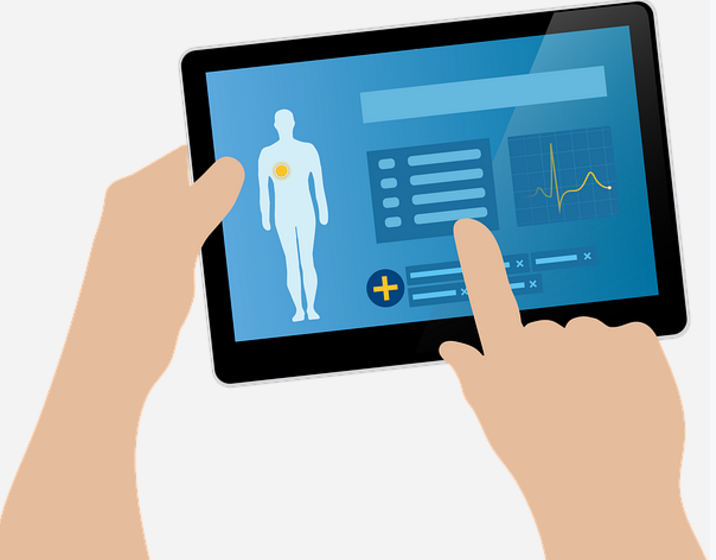

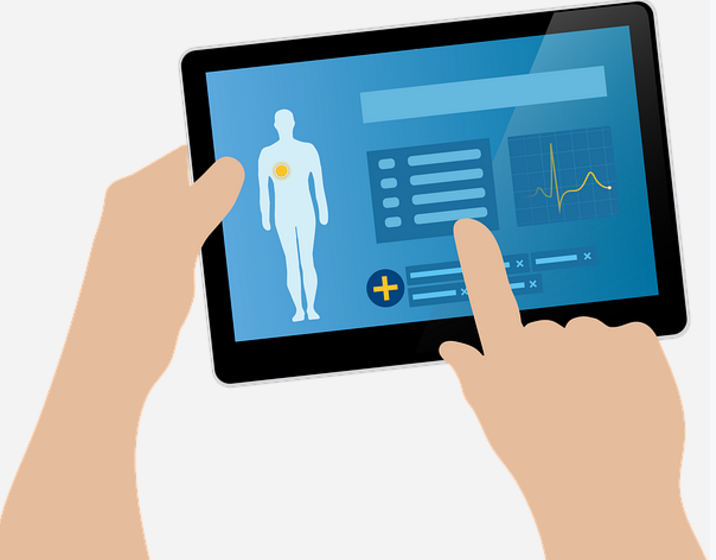

In interviews and meetings with stakeholders and through observing clinicians and patients interact, we identified layers and layers of requirements for a system that would achieve our goal. Our solution was Project Emerge, a system that integrates data from several sources into one easy-to-read computer display. It combined data from existing technologies, such as the electronic patient record, with new ones, such as sensors that track patient activity or the angle of a bed. In the same way that pilots get all essential information in cockpit displays, Emerge lets clinicians quickly see if patients are getting all the care necessary to prevent the seven harms. A second computer display helps patients and families engage with their care team and take a more active role in their care.

One module of Emerge, focusing on the prevention of ICU-acquired weakness, demonstrates the elegance of a systems engineering approach. Research tells us that patients regain their strength earlier and have fewer related complications when they start moving as soon as safely possible during their stay in the hospital. Yet in most ICUs there isn’t a culture to support early mobility; clinicians are not conditioned to ask every day whether their bedbound patients are able to get moving, or whether they are meeting their mobility goals. There are no devices or displays that inform patients of their progress or warn them if they are falling short.

The Emerge system compels clinicians to set a patient’s mobility goals and pulls data from different sources into the dashboard, where the ICU-Acquired Weakness display turns red if the patient is not on track. Clinicians can tap the touch screen, drill down for details, and address next steps. Meanwhile, patients and family members can pick up a tablet computer and learn about the importance of mobility; family members take part in getting their loved ones out of bed or walking in the ICU.

The whole team is part of this technology-enabled culture change, making early mobility something that’s routine rather than an afterthought. With this app, the percentage of patients who were given mobility goals went from 40% to 100%, and those receiving mobility therapy increased from 48% to 80%. Those who had significant functional declines in their mobility decreased from 19% to 10%.

Of course, ICU-acquired mobility is just one harm, and this module is just one of many that share data and knowledge, make processes more efficient, prevent harm, and keep families top-of-mind. These modules must be integrated so that clinicians are not overwhelmed with more information and tasks than they can manage.

Emerge demonstrated that the systems engineering approach can help reduce specific harms, but there are many other goals that it could help achieve — for example, improving productivity, enhancing patient experience, improving bed management, and enhancing transitions of patient care between providers.

Such efforts could accelerate if more manufacturers of health care technologies were willing to let their products “talk” to one another. Generally speaking, they don’t. While we were able to integrate data from several sources into Emerge, the work was highly technical and labor intensive. More innovation could occur across health care, and health care would become less fragmented, if technologies shared information more readily.

We hope our experience will give them one more reason to do so.

Peter Pronovost is an intensive care physician and the C. Michael and S. Ann Armstrong Professor of Patient Safety at Johns Hopkins University. He serves as the Johns Hopkins Medicine Senior Vice President for Patient Safety and Quality and the Director of the Armstrong Institute, and helps to lead patient safety efforts globally.

Peter Pronovost is an intensive care physician and the C. Michael and S. Ann Armstrong Professor of Patient Safety at Johns Hopkins University. He serves as the Johns Hopkins Medicine Senior Vice President for Patient Safety and Quality and the Director of the Armstrong Institute, and helps to lead patient safety efforts globally.

Recent Comments